|

Jose Dàvila:

|

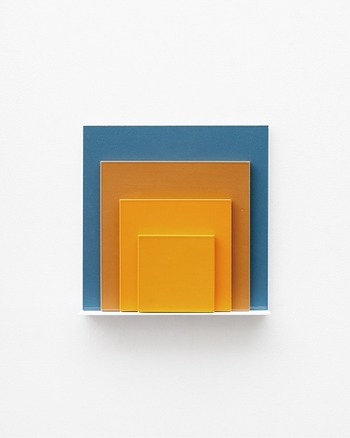

| Homage to the Square | 2024 | Photo by Agustín Arce | ©Jose Davila |

Venue: nca | nichido contemporary art

Date: 5.24 (Sat.) – 7.5 (Sat.) 2025

*Gallery hours: Tue. – Sat. 11:00 – 19:00 (Closed on Mon., Sun., and National Holidays)

nca | nichido contemporary art is pleased to present Albers’ Works, a solo exhibition by artist Jose Dàvila.

In his work Dávila embodies artistic and architectural elements appropriated and recontextualized from iconic artists throughout history, and by so doing he reflects on the definition of conceptual art namely that it is the content and not the form what gives importance and meaning to a work of art. Through his practice, Dávila investigates aspects such as space, volume, balance and materiality, which are all an example of physical force, creating works whose shape is in constant conversation with art history.

This exhibition presents a selection of works especially assembled for this occasion from Dávila’s series Homage to the Square, which was recently displayed at the Museum of Modern Art, Gunma from March 1 to April 6.

I Prefer to see with my Eyes Closed.

By Jose Dàvila

Josef Albers was not content with merely looking; he insisted on seeing.

Seeing color not as a presence but as an experience; seeing a square not as a shape but as an instrument to reflect on the process of learning and thinking how to see.

I wonder when Albers first influenced me without my realizing it.

Perhaps it was when, as a child, I contemplated the colorful tiles in a square where I learned to ride a bicycle or when noticing the play of shadows on a facade.

Perhaps it was later, as an architecture student visiting Luis Barragán's house, where a reproduction of a painting from Albers' Homage to the Square series hung. Reportedly, this “unauthorized” reproduction did not actually bother Albers, a friend of Barragán.

Not knowing when I do, however, yet know that the clarity of his Homage to the Square paintings and prints is able to instantly transport me to those every day, omnipresent moments, to remind me that art has always been there, waiting to be seen.

In both his work and pedagogy, such a legacy invites us to deeply reconsider how we understand space, relationships, and meaning — recurring themes in my own work.

Albers was born in Bottrop, Germany, in 1888. He studied to become a schoolteacher and worked in that profession. His journey took him from being a student of the Bauhaus in Weimar, where he replaced his teacher Johannes Itten alongside László Moholy-Nagy in 1923, to the legendary Black Mountain College in North Carolina and, ultimately, Yale.

Albers's contribution at Black Mountain College was transformative. The institution was an experimental laboratory that redefined what artistic education could be. The Black Mountain model was revolutionary because it rejected traditional hierarchies and encouraged interdisciplinary collaboration.

By the time the Albers arrived in Asheville, he had acquired enough English to answer the question on his ambitions at the school with the eloquently inarticulate line: "To make open the eyes."

Albers taught that art was not an end in itself but a tool. He embodied the aphorism that "the art of teaching is the art of assisting discovery."

Students like Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, Susan Weil, Ruth Asawa, or John Cage—whom he invited to teach—witnessed a rigorous yet profoundly liberating method in which every material and form had something to tell if approached with fair attention.

After Josef and Anni Albers had settled in North Carolina, they visited Mexico for the first time in December 1935, visiting Mexico City, Teotihuacán, Acapulco, Oaxaca, and Mitla and Monte Albán.

After their 1935 trip, Josef Albers wrote to Vassily Kandinsky, describing Mexico as the promised land of abstract art, noting that it had existed there for thousands of years.

Between 1935 and 1967, Josef and Anni made at least 14 trips to Mexico, well documented in extraordinary photographs, diaries, and sketches, that nurtured and influenced their work and teaching content.

As a Mexican artist, I am compelled to wonder whether there is an underlying subconscious connection between my work and that of Albers, as a byproduct of my visual culture and his fascination with it.

At first glance, the Homage to the Square series may seem simple; it consists of paintings repeating the pattern of carefully colored concentric squares.

The purpose of this series was not to delight the eye but to test our perception and make us mindful of how we experience color.

Over 25 years, with this deeply meditative study on chromatic relationships and visual perception, Albers explored how colors interact, change, and transform based on their context. It is a simple thought, yet it is, or becomes, a study of almost infinite profundity. It is not a mere treatise on color. It is a tool to unlock the magic of awareness.

Like an educational device, these paintings become a mirror that confronts us with ourselves. What they reveal is our way of seeing.

The repetition of his Homage to the Square series creates a deliberate calm—a space where the mind can rest. His use of color, repetition, and lines is joyous, meditational, as well as serene. It is a universal gesture.

In these paintings and prints, we are able to find an immensity of perceptual relationships that remind us that the simplest things in life can also contain the most complex messages.

I also find another fascinating paradox in Albers: his precise and rational work is deeply emotional, which leads me to reflect on how we relate to our contradictions. Although his method was so exacting that it might seem rigid, his results always leave room for interpretation. Limited in form but unlimited in possibilities, each square serves as a formal boundary while opening an endless space for thought.

On a more profound level, Albers' work connects us with an almost spiritual idea: the experience of the present through the essential. This quality links Albers to minimalism as a philosophical movement, where a reduction to the fundamental does not eliminate emotion but intensifies it.

Each Albers Homage to the Square is a repetition that acts as a visual mantra that, when contemplated, can anchor us in the here and now. Like meditation, observing this work can be a way to transcend distraction and enter a state of connection with what is essentially human: our perception.

Albers stated, "We see color as we see it, not as it is..." This series serves as a testament to that idea. Through generous and almost mechanical repetition, Albers encourages us with these paintings to explore more than just how colors interact with one another but how the same shade can look different based on its surrounding colors. More importantly, he highlights how contextual relationships always influence our perception of the world.

Albers taught there is no "correct answer" for experiencing art—only possibilities—as far as we become aware. I strive to incorporate that same generosity into my practice by creating works that do not impose meaning but instead invite the viewer to discover it. This duality between control and freedom reminds me of Georges Perec's words: "Space has as much to do with boundaries as with openness." So, I intend to maintain a balance in my own practice by creating works that act as both containers and catalysts for experience. I focus on space not as a void but as an opportunity to develop meaningful associations.

I recall a particular piece I created that was inspired by Albers. While working on it, I thought about his pioneering notion that art does not exist in isolation as much as in relationships. Just as humans exist in relationship with one another and their environment, every element in a work must be in dialogue with the other elements. This piece, presented at The Bass Museum Park in Miami in 2012, was a courtyard of ceramic tiles arranged in staggered levels that transformed Albers Homage to the Square into a three-dimensional composition with vivid yellow and orange colors that played with daylight. Observing how people interacted with that "courtyard," once open to the public—the way children turned the staggered levels into a device for an improvised game of tag by running across it —I noticed something Albers would have appreciated: that art is not complete until someone inhabits it. In the act of inhabiting, art finds its most profound purpose.

My reinterpretation of his legacy does not seek to replicate his artistic language as much as to expand the scope of his inquiry beyond the two-dimensional by giving squares and colors a tangible, moving, three-dimensional life.

It aims to introduce an additional layer of content, not only to reexamine the act of seeing but also to invite reflection on how we inhabit our environments and how our lived experiences are shaped by our relationships with the objects around us.

Georges Perec argued that space is more than a physical place; it is also a mental construction or a narrative of relationships. In Species of Spaces, he wrote that "we live in space, but we do not always see it."

We simultaneously inhabit multiple physical, emotional, and cultural spaces. These spaces are not only traversed but built upon, one relationship at a time.

Art resides in the relationships we create through it, and I find the most generous and meaningful space to exist within those relationships.

I infer a simple premise from Albers’s work that I apply in my own: that is to make the work easy to see and hard to forget. He continuously reminds me that art need not be monumental to be monumentally meaningful.

December 2024

________________________________________

Jose Dàvila

b. 1974, Guadalajara, Mexico. Currently lives in Guadalajara, Mexico

Following a degree in architecture obtained from Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente (ITESO), he becomes a self-taught artist whose practice spans sculpture, installation, painting, and photography.

More than 60 solo shows have been held at major museums such as Museum Haus Konstrukti (Switzerland), Dallas Contemporary (Texas), JUMEX Museum (Mexico City), Hamburger Kunsthalle (Hamburg), Museum Del Novecento (Florence), and his work has been shown on occasion of international art events such The 16th Lyon Biennial (2022), The 13th Havana Biennial (2019), The 10th Mercosur Biennial (2015).

His work has become part of prominent museum and private collections such as of MUAC (Mexico City), Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (Madrid/Spain), Instituto Inhotim (Brumadinho, Brazil), Pérez Art Museum Miami (Miami, Florida), Buffalo AKG Art Museum (Buffalo, New York), San Antonio Museum of Art (San Antonio, Texas), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (New York), Centre Pompidou (Paris), Hamburger Kunsthalle (Hamburg), 、Grand Duke Jean Museum of Modern Art (Luxemburg), Taguchi Art Collection and others.

He was awarded the 2017 BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art's New Annual Artists' Award, and is a 2016 Honoree of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington DC. In 2014 he was awarded with the 2014 EFG ArtNexus Latin America Art Award, and has been the recipient of support from the Andy Warhol Foundation, a Kunstwerke residency in Berlin, and the National Grant for young artists by the Mexican Arts Council (FONCA) in 2000. In 2022, Hatje Cantz published a major monograph illustrating the past twenty years of Dàvila’s practice.